Accelerating Batch Processing of Images in Python — with gsutil, numba and concurrent.futures

[til python How to accelerate batch processing of almost a million images from several months to just around a few days

In a data science project, one of the biggest bottlenecks (in terms of time) is the constant wait for the data processing code to finish executing. Slow code, as well as intermittent connection to web and remote instances affect every step of a typical data science pipeline - data collection, data pre-processing/parsing, feature engineering, etc. Sometimes, the gigantic execution times even end up making the project infeasible and often forces a data scientist to work with only a subset of the entire dataset, depriving the data scientist of insights and performance improvements that could be obtained with a larger dataset.

In fact, time bottlenecks resulting from long execution times are even more accentuated for batch processing of image data, which are often read as numpy arrays of large dimensions.

Problem Description

About 2 months ago, my colleagues and I took part in the Advanced Category for the Shopee National Data Science Challenge 2019. The competition involves extracting product attributes from product title, and we were given three main categories of items: mobile, fashion and beauty products. In addition, we were also given the image path of each item and the associated image file - all 77.6 GB of it!

It was our first ever competition on Kaggle, and we started out feeling confident with the hybrid text-and-image model we had in mind - only to face bottlenecks in downloading and processing the large image datasets into Numpy arrays in order to feed them as inputs for our model. Here are some of my notes on the approach I attempted to resolve these issues, with particular focus on how I used numba and concurrent.futures to accelerate batch processing of almost a million images from several months to just around a few days.

Data Processing Workflow

To start off, here are the general steps in our data processing workflow:

- Download large image datasets from source using wget command

- Upload large volume of image files to Google Cloud Storage using gsutil

- Import each image file from Cloud Storage to Colab

- Convert each image to standardized numpy array

Step 1: Using wget command to download large image datasets

The first bottleneck we faced was downloading the image files from the Dropbox links provided by Shopee. Due to data leaks for the fashion category, we had to download the updated CSV files and image files again. One of the archive files containing images for the training set in the fashion category (including the original test set that had its attribute labels leaked) amounted to 35.2 GB, and our multiple attempts throughout the week at using Google Chrome to download the .tar.gz archive files containing the image files failed due to “Network error”.

This bottleneck was resolved using the wget command on Ubuntu in Windows 10 WSL (Windows Subsystem for Linux). The best part about using the wget command for downloading large files is that it works exceedingly well for poor or unstable connections, as wget will keep retrying until the whole file has been retrieved and is also smart enough to continue the download from where it left off.

I opened 2 instances of Ubuntu for WSL and ran wget commands on each instance to download the .tar.gz archive files containing the images for the three categories. All four archive files were downloaded successfully after 16 hours, surviving poor connection and network errors. Extracting the image files from the archive files using the tar -xvzf command took another 12 hours in total.

Tip: Working on command line is usually faster than working on GUI - so it pays to know a bit of command line as a speed hack.

Step 2: Upload image files to Google Cloud Storage using gsutil cp

My team uses Google Colab to share our Jupyter notebooks and train our models. Colab is great for developing deep learning applications using popular frameworks such as TensorFlow and Keras - and it provides free GPU and TPU.

However, there are some limits that we face while using Colab:

- Memory limit:~12 GB RAM available after startup

- Timeout: You are disconnected from your kernel after 90 minutes of inactivity - that means we can’t just take a nap while letting our processes run and waiting for our files to be uploaded (Constant vigilance!).

- Reset runtimes: Kernels are reset after 12 hours of execution time - that means all files and variables will be erased, and we would have to re-upload our files onto Colab. Continuously having to re-upload tens of thousands of image files onto Colab while on constant standby is too tedious and slow.

- Google Drive: Technically, we could mount our Google Drive onto Colab to access the files in Google Drive. As none of us pay for additional storage space on Google Drive, we do not have enough storage space for 77.6 GB of image files. Accessing the files through a portable drive is also not a plausible option, as that would add additional consideration in terms of data connectivity between the desktop/laptop and the portable drive.

In short, we needed a solution whereby we could store and access our files whenever needed, while at the same time paying only for what we use rather than fork out additional money just to pay for more storage on Google Drive.

In the end, we decided on using Google Cloud Storage (GCS) to store and access our image files. GCS is a RESTful online file storage web service on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP) which allows worldwide storage and retrieval of any amount of data at any time. Google provides 12 months and US$300 of GCP credits as a free tier user, which is perfect for our case since the credits would last for at least a month if we use them wisely.

First, I created a GCS bucket by using gsutil mb on Cloud SDK (the instructions on installing and setting up Cloud SDK can be found here and here respectively - I used apt-get to install Cloud SDK on my Ubuntu image, while Cloud SDK is available in Colab).

# Replace 'my-bucket' with your own unique bucket name

! gsutil mb gs://my-bucket

Let’s say I decide to call my storage bucket ‘shopee-cindyandfriends’:

! gsutil mb gs://shopee-cindyandfriends

Next, I proceeded to upload all my image files from each folder directory to my storage bucket using gsutil cp. Since I have a large amount of files to transfer, I performed a parallel copy using the gsutil -m option. The syntax is as follows:

# Replace 'dir' with directory to copy from

! gsutil -m cp -r dir gs://my-bucket

Let’s say I’m uploading all the image files from the fashion_image directory to my storage bucket:

! gsutil -m cp -r fashion_image gs://shopee-cindyandfriends

Now, wait patiently and go about your usual day (maybe take a nap or grab some coffee to recharge) while gsutil uploads your files. Don’t worry too much about poor or unstable connections as:

- gsutil does retry handling - the gsutil cp command will retry when failures occur.

- If your upload is interrupted or if any failures were not successfully retried at the end of the gsutil cp run, you can restart the upload by running the same gsutil cp command that you ran to start the upload.

Uploading the image files to the GCS bucket using gsutil cp command took around 12–15 hours in total, surviving poor connection and network disruptions. Do not try uploading large amounts of files using the GCP web console - your browser will crash!

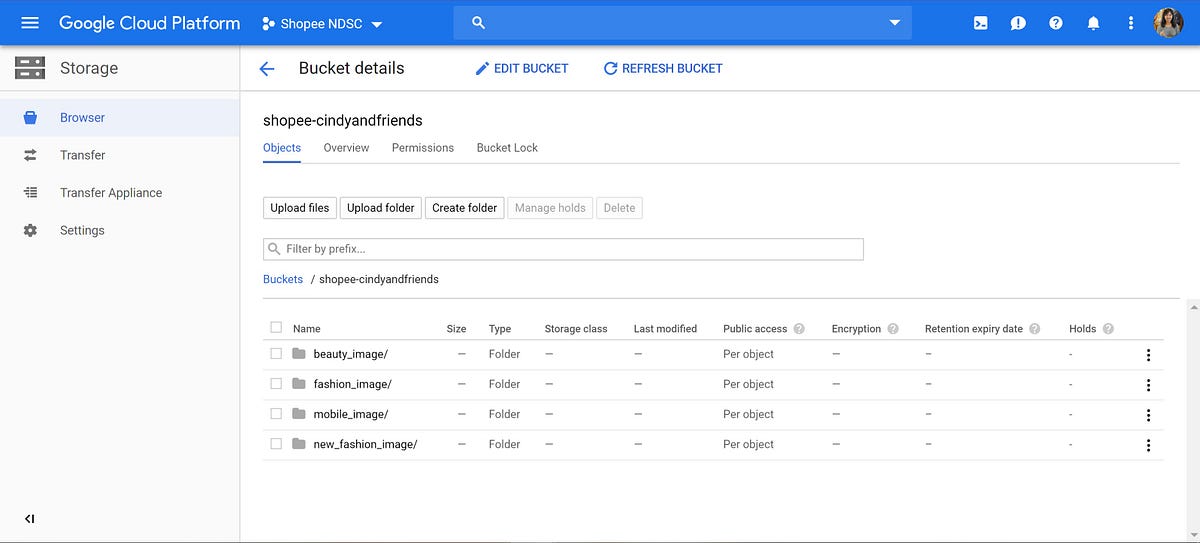

All 4 folders in our storage bucket - success!

All 4 folders in our storage bucket - success!

Step 3: Import each image file from Cloud Storage to Colab

Now that we have our complete set of image files uploaded on Cloud Storage, we need to be able to access these files on Colab via the image path of each item in the dataset. The image path of each item is extracted from the dataframe which in turn was extracted from the CSV file of the corresponding dataset.

def define_imagepath(index):

'''Function to define image paths for each index'''

imagepath = fashion_train.at[index, 'image_path']

return imagepath

Remember the problem of poor connection? To ensure that retry handling is also performed during import operations from GCP, I used the retrying package as a simplified way to add retry behavior to the Google API Client function. Here’s the Python code I used:

from retrying import retry

from google.colab import auth

@retry(wait_exponential_multiplier=1000, wait_exponential_max=10000)

def gcp_imageimport(index):

'''Import image from GCP using image path'''

from googleapiclient.discovery import build

# Create the service client.

gcs_service = build('storage', 'v1')

from apiclient.http import MediaIoBaseDownload

colab_imagepath = '/content/' + define_imagepath(index)

with open(colab_imagepath, 'wb') as f:

request = gcs_service.objects().get_media(bucket = bucket_name, object = define_imagepath(index))

media = MediaIoBaseDownload(f, request)

done = False

while not done:

_, done = media.next_chunk()

Okay, let’s proceed to define our functions for pre-processing the image into numpy arrays.

Step 4: Convert each image to standardized numpy array

It is observed that the images in the dataset are of different formats (some are RGB while others are RGBA with an additional alpha channel) and different dimensions. As machine learning models usually require inputs of equal dimensions, pre-processing is required to convert each image in the dataset to a standardized format and resize the images into equal dimensions. Here’s the Python function for RGB conversion, resizing and numpy array conversion:

from PIL import Image

def image_resize(index):

'''Convert + resize image'''

im = Image.open(define_imagepath(index))

im = im.convert("RGB")

im_resized = np.array(im.resize((64,64)))

return im_resized

Seems easy to follow so far? Okay, let’s put all the above steps together and attempt to write the processing code for the entire image dataset:

def image_proc(image, start, end):

gcp_imageimport(image)

#download_blob('shopee-cindyandfriends', image)

im_resizedreshaped = image_resize(image)

if (image + 1) % 100 == 0 or (image == N - 1):

sys.stdout.write('{0:.3f}% completed. '.format((image - start + 1)*100.0/(end - start)) + 'CPU Time elapsed: {} seconds. '.format(time.clock() - start_cpu_time) + 'Wall Time elapsed: {} seconds. \n'.format(time.time() - start_wall_time))

time.sleep(1)

return im_resized

def arraypartition_calc(start, batch_size):

end = start + batch_size

if end > N:

end = N

partition_list = [image_proc(image, start, end) for image in range(start, end)]

return partition_list

###### Main Code for Preprocessing of Image Dataset ######

import sys

import time

N = len(fashion_train['image_path'])

start = 0

batch_size = 1000

partition = int(np.ceil(N/step))

partition_count = 0

imagearray_list = [None] * partition

start_cpu_time = time.clock()

start_wall_time = time.time()

while start < N:

end = start + batch_size

if end > N:

end = N

imagearray_list[partition_count] = [arraypartition_calc(image) for image in range(start, end)]

start += batch_size

partition_count += 1

For the code sample above, I attempted to process the ~300,000 images in the image dataset sequentially in batches of 1,000 and kept track of progress using a rudimentary output indicator within the image processing function. List comprehension was used to create a new list of numpy arrays for each processing batch.

After more than 7 hours of leaving the code running on a CPU cluster overnight, barely around 1.1% (~3300) of the images were processed - and that’s just for one dataset. If we were to process almost 1 million images sequentially using this approach, it’ll take almost 3 months to finish processing all the images - and that is practically infeasible! Besides switching to a GPU cluster, are there any other ways to speed up this batch processing code so that we could pre-process the images more efficiently?

Speed Up with numba and concurrent.futures

In this section, I introduce two Python modules that helps speed up computationally intensive functions such as loops - numba and concurrent.futures. I will also document the thought process behind my code implementation.

JIT compilation with numba

Numba is a Just-in-Time (JIT) compiler for Python that converts Python functions into machine code at runtime using the LLVM compiler library. It is sponsored by Anaconda Inc., with support by several organizations including Intel, Nvidia and AMD.

Numba provides the ability to speed up computationally heavy codes (such as for loops - which Python is notoriously slow at) close to the speeds of C/C++ by simply applying a decorator (a wrapper) around a Python function that does numerical computations. You don’t have to change your Python code at all to get the basic speedup which you could get from other similar compilers such as Cython and pypy - which is great if you just want to speed up simple numerical codes without the hassle of manually adding type definitions.

Here’s the Python function for image conversion and resizing, wrapped with jit to create an efficient, compiled version of the function:

from numba import jit # JIT processing of numpy arrays

from PIL import Image

@jit

def image_resize(index):

'''Convert + resize image'''

im = Image.open(define_imagepath(index))

im = im.convert("RGB")

im_resized = np.array(im.resize((64,64)))

return im_resized

I tried using njit (the accelerated no-Python mode of JIT compilation) and numba parallelization (parallel = True) to achieve the best possible improvement in performance; however, compilation of the above function fails in no Python mode. Hence, I had to fall back to using the jit decorator, which operates in both no-Python mode and object mode (in which numba compiles loops that it can compile into functions that run in machine code, while running the rest of the code in the Python interpreter). The reason why njit fails could be due to numba being unable to compile PIL code into machine code; nevertheless, numba is able to compile numpy code within the function and a slight improvement in speed was observed with jit.

Since numba parallelization can only be used in conjunction with no-Python JIT, I needed to find another way to speed up my code.

Parallel processing and concurrent.futures

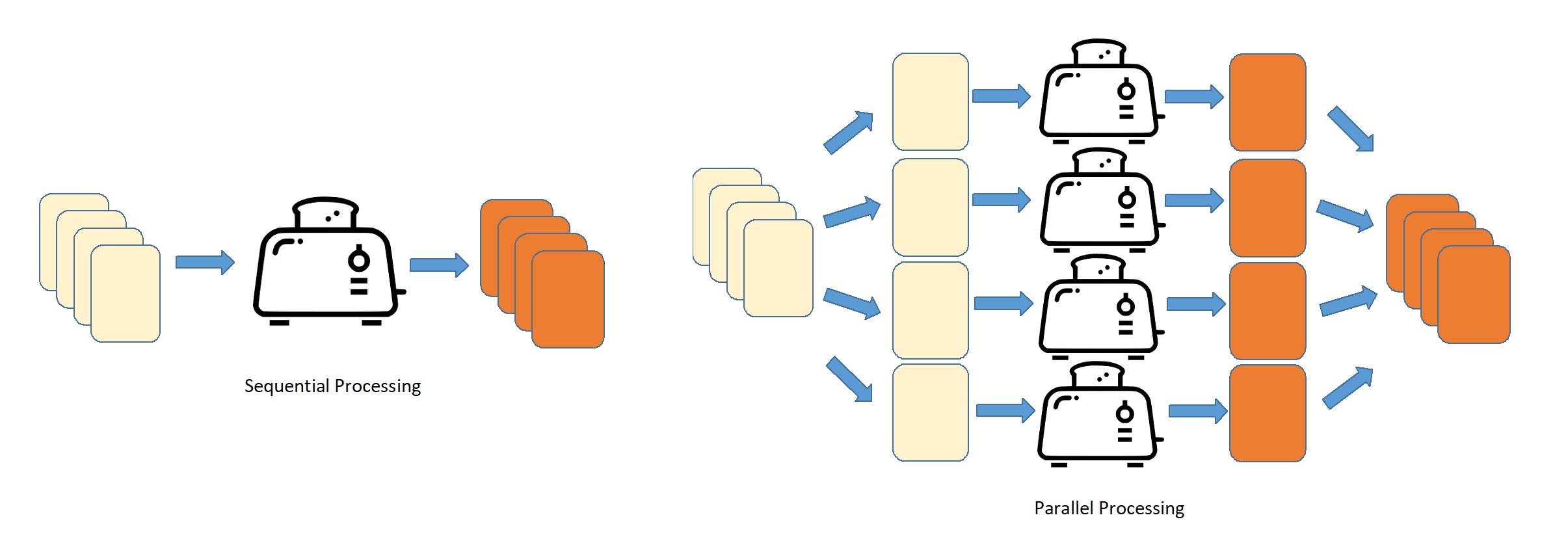

To understand how to process objects in parallel using Python, it is useful to think intuitively about the concept of parallel processing.

Imagine that we have to perform the same task of toasting bread slices through a single-slice toaster and our job is to toast 100 slices of bread. If we say that each slice of bread takes 30 seconds to toast, then it takes 3000 seconds (= 50 minutes) for a single toaster to finish toasting all the bread slices. However, if we have 4 toasters, we would divide the pile of bread slices into 4 equal stacks and each toaster will be in charge of toasting one stack of bread slices. With this approach, it will take just 750 seconds (= 12.5 minutes) to finish the same job!

Sequential vs Parallel Processing - illustrated using toasts

Sequential vs Parallel Processing - illustrated using toasts

The above logic of parallel processing can also be executed in Python for processing the ~300,000 images in each image dataset:

- Split the list of .jpg image files into n smaller groups, where n is a positive integer.

- Run n separate instances of the Python interpreter / Colab notebook instances.

- Have each instance process one of the n smaller groups of data.

- Combine the results from the n processes to get the final list of results.

What is great about executing parallel processing tasks in Python is that there is a high-level API available as part of the standard Python library for launching asynchronous parallel tasks - the concurrent.futures module. All I needed to do is to change the code slightly such that the function that I would like to apply (i.e. the task to be implemented on each image) is mapped to every image in the dataset.

#N = len(beauty_train['image_path']) # for final partition

N = 35000

start = 0

batch_size = 1000

partition, mod = divmod(N, batch_size)

if mod:

partition_index = [i * batch_size for i in range(start // batch_size, partition + 1)]

else:

partition_index = [i * batch_size for i in range(start // batch_size, partition)]

import sys

import time

from concurrent.futures import ProcessPoolExecutor

start_cpu_time = time.clock()

start_wall_time = time.time()

with ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

future = executor.map(arraypartition_calc, partition_index)

From the above code, this line:

with ProcessPoolExecutor() as executor:

boots up as many processes as the number of cores available on the connected instance (in my case, the number of GPU cores in Colab that are made available during the session).

The executor.map() takes as input:

- The function that you would like to run, and

- A list (iterable) where each element of the list is a single input to that function;

and returns an iterator that yields the results of the function being applied to every element of the list.

Since Python 3.5, executor.map() also allows us to chop lists into chunks by specifying the (approximate) size of these chunks as a function argument. Since the number of images in each dataset are generally not round numbers (i.e. not multiples of 10s) and the order of the image arrays are important in this case (since I have to map the processed images back to the entries in the corresponding CSV dataset, I manually partitioned the dataset to account for the final partition which contains the tail-end remainder of the dataset.

To store the pre-processed data into a numpy array for easy “pickling” in Python, I used the following line of code:

imgarray_np = np.array([x for x in future])

The end result was a numpy array containing lists of numpy arrays representing each pre-processed image, with the lists corresponding to the partitions which form the dataset.

With these changes to my code and switching to the GPU cluster in Colab, I was able to pre-process 35,000 images within 3.6 hours. Coupled with running 4–5 Colab notebooks concurrently and segmenting the entire image dataset into subsets of the dataset, I was able to finish pre-processing (extracting, converting and resizing) almost 1 million images within 20–24 hours! Not too bad a speed-up on Colab, considering that we initially expected the image pre-processing to take impracticably long amounts of time.

Some Reflections and Takeaways

It was our first time taking part in a data science competition - and definitely my first time working on real-life datasets of such a large scale compared with the clean-and-curated datasets that I worked with for my academic assignments. There might be plenty of spotlight on state-of-the-art data science algorithms within a data science project; however, I’ve also learnt through the experience that data processing can also often make or break a data science project if it becomes a bottleneck in terms of processing time.

On hindsight, I could have created a virtual machine on Google Cloud Platform and run the codes there, instead of relying solely on Colab and having to keep track of code execution in case I hit the 12-hour time limit for the GPU runtime.

In conclusion, here are my takeaways:

- Command line interface is typically faster than GUI - if you can, try to work on the command line as much as possible.

- Facing poor connection issues? Retry handling can help save you the heartache from having to re-upload or re-download your files.

- Numba and concurrent.futures are useful when you are looking for a hassle-free way to speed up pre-processing of large datasets without manually adding type definitions or delving into the details of parallel processing.

For reference, the codes accompanying this write-up can be found here.